When Prompt Engineering Stops Being Enough

This post is for developers who already use LLM-based tools daily and have started noticing that "just write a better prompt" doesn't always scale.

I use Claude and Cursor in development every day. Not for demos. For real tasks that go to production.

Over time I noticed that I don't have one fixed workflow. I choose the approach depending on the task, and three examples make the difference clear.

The difference between them is not the model. It's the complexity of the system around the task.

And that complexity changes the way I build and deliver context.

This is not a story about how I learned prompting. This is a decision framework for choosing the right approach.

Three Tasks to Three Different Approaches

Level 1: A one-off script

A typical task:

I need a small script to scrape data from a website.

What I do:

I open Cursor, write a single prompt with a clear technical description, get the code, run it. If needed, I add one or two follow-up comments to adjust the output, but I never even open the script itself. I'm not going to maintain it. I only need the result once.

Done.

No persistent context. No documentation. No rules.

And it works perfectly.

Here prompt engineering is everything. There is nothing else to engineer.

Level 2: My blog (an evolving product)

The second case is different.

I'm working on a new feature for my blog: https://blog.rezvov.com

This is no longer a single file task.

There is:

- a defined stack (Next.js SSG+SSR, pnpm, Nginx, JSON as a database)

- content rules: store content in Markdown, render to HTML

- SEO plumbing: generate a sitemap, configure robots.txt

- configuration and integrations: load config, wire the build and runtime correctly

- deployment via GitHub CI

If I try to cram all of this into a prompt every time, it turns into a reliability problem.

Because this approach is not reliable. I will forget something sooner or later, the model will fill the gaps with assumptions, and the result can look correct while quietly violating the project rules. And when I return to this a month later to extend it, I won't even remember what the original plan was.

So I don't rely on memory or a "perfect prompt" here.

Instead I keep the rules as committed artifacts:

CLAUDE.md- Cursor rules

- base project docs

In practice this looks like a few lines in CLAUDE.md at the root of the repo:

## Blog Post Workflow

- File: content/posts/YYYY-MM-DD-slug.md

- Frontmatter MUST include: title, slug, date, tags, excerpt, description, author

- Feature image: 896x384 pixels, .webp format

- Validation: pnpm lint:posts <slug> MUST pass before commit

- Draft workflow: start with draft: true, remove when ready

Now the agent reads the rules and behaves correctly without me restating them. I don't need to remember the image dimensions or the naming convention. The system remembers for me.

At this level prompt engineering stops being enough. You need persistent artifacts.

Level 3: A commercial multi-repo system

At this scale the problem changes.

A large production project is not just backend and frontend. In my case it's 18 repositories on the backend, plus another 6 on the frontend.

And it's not just services. There are dedicated repos for documentation, deployment, tests, proto contracts, and even a working environment for Claude/Cursor (rules, specs, hooks). A single feature can easily touch several services, their contracts and the CI pipeline at the same time.

At this point the problem is no longer writing code. The problem is context.

If I try to push all requirements and instructions into the model at once, it will drop parts, even if it is the smartest one. The worst part is I cannot predict which parts will be lost and when. The real question is what part of the system it needs for this task and in what order.

If that slice is wrong, the model produces code that looks architecturally correct and even passes local checks, but then fails in CI, breaks contracts or violates platform standards. Not because the model is weak, but because it was given a convincing but wrong view of the system.

At this level documentation alone is not enough. You need a context system. I describe how I build one later in this post.

Prompt Engineering vs Context Engineering

This is how I think about prompt engineering vs context engineering when choosing an approach.

Prompt engineering

How to ask the model to do something inside a single session.

Context engineering

How to design the environment around the model so it behaves correctly for this system.

I treat context as a limited resource that has to be managed as a system. The model is not the bottleneck. The way I assemble and deliver context is.

The practical difference

| Prompt | Context |

|---|---|

| Lives for one session | Committed to git |

| One large text | Layered system |

| Manual recall | Automatic delivery |

| Hope for obedience | Enforced by checks |

How I Build the Context System

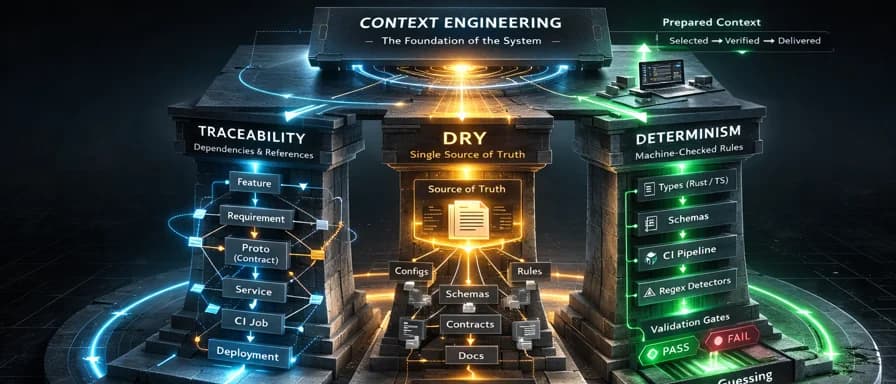

My context engineering setup is built on three pillars.

Traceability. Every artifact points to the thing it depends on and to the thing that depends on it. A change in a proto contract points to the services that use it. A deployment step points to the configuration it needs. A feature points to the product requirement it implements. So I can assemble the right context for a task instead of loading the whole system.

DRY. There is only one source of truth for each type of information. No duplicated configs, no copied rules, no parallel descriptions of the same contract. If something changes, it changes in one place and the rest of the system references it.

Determinism. I design the stack so that as little as possible is left to interpretation. Strict typing, explicit schemas, reproducible pipelines and machine-checkable rules reduce the space where the model can guess. I also write regex-based detectors that flag suspicious rule violations so the agent can evaluate them instead of guessing from scratch.

The first step is to split everything into atoms instead of keeping one big description in the model:

- product requirements (Markdown)

- architecture constraints (Markdown, diagrams)

- code rules (Markdown, linters/formatters config)

- configuration rules (YAML, env files)

- deployment and runtime procedures (CI YAML, Helm, bash)

- API contracts (proto, OpenAPI specs)

- infrastructure (Terraform, Ansible, Helm)

Each atom lives in its own place. Traceability links them: a contract change points to the services that consume it, a deployment step points to its config, a feature points to its product requirement.

Rules are not just text. Wherever possible they are enforced by scripts and tools in CI. If a rule can be broken silently, it will be.

All of this is wired into the working environment through Claude and Cursor rules. Hooks decide what context to load and run audit procedures before and after the task.

At this scale context is not a prompt. It is a system that selects, verifies and delivers the right slice of information for the change.

Important: Prompt Engineering Is Not Dead

It is still perfect for:

- scripts

- small tools

- isolated tasks

- research

- brainstorming

- or just for fun

But the moment you build:

- a real product

- a platform

- a distributed system

prompt-only workflows collapse under their own weight.

Context engineering is not a trend. It is an architectural necessity once the task outgrows a single file.